Right, so there was never a Roman king named Wenceslaus. The person with this title was actually King of Bohemia, and of Germany. His nickname was "the Idle," and, unsurprisingly, there is little to recommend him to history books. Yet in 1378, he was endowed with the confusing—yet official—nomenclature, Romanorum Rex. As a job description, this is pretty wide of the mark. In the 14th century Rome was certainly not part of either German of Bohemian territory. Rome was in fact firmly in the control of the papacy, as it had been for centuries. On the flip side, the larger part of Germany, and all of Bohemia, had never been Roman at all, and Wenceslaus lived about a thousand years after the end of the Western Roman Empire anyway. And yet, the title King of the Romans was the official style of all German kings from the 800s down to Charles V. Somehow, in the Middle Ages, Rome acquired a new name, and a new location: Germany.

Pretending to be the successors to Rome is a strikingly common impulse, and not only in Europe. The Holy Roman Empire is the most obvious example (the Romanorum Rex—"King of Germany"—would usually also be elected Romanorum Imperator). But political structures throughout the former Empire used a Roman rhetoric to defend their power; when Constantinople fell, Ivan III's Moscow proclaimed itself the "Third Rome"—at the same time that the conquering Sultan Mehmed II named himself Kayser-i Rum: Caesar of Rome. And even within the structure of the Holy Roman Empire, claims to additional Roman linkage were often wheeled out. The strangest example is perhaps the Privilegium Maius, a document forged by the Habsburgs in the 14th century claiming that Austria had been declared an indivisible patrimony, and donated to their family, by the emperors Julius Caesar and Nero.

But translating the Roman legacy into Germany is rather tricky, ideologically-speaking, even when Nero is not involved. There is a simple reason for this: in antiquity, Germans were primarily famous for killing Romans. German resistance meant that the Roman frontier never got beyond the Rhine or the Danube. In the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and especially in the Romantic era, Germany culturally defined itself as precisely the opposite of Romanism: where Rome (and its successor, France) were universalist, idealist, urban, corrupt, and debauched, Germany should be mythic, authentic, natural, simple, and powerful; Rome was a civilization of masonry; Germany, of trees. Thus, in the land whose political structures solemnly assumed Romanized titles, there has long been a simultaneous disavowal of all that those titles stand for.

This tension became clear to me when I was in Trier. As background: Trier was founded by Augustus as Augusta Treverorum, named after the Celtic Treveri people who lived there (and after himself). It quickly evolved into a major center of the Roman empire, even becoming an imperial capital in the 4th century AD, and became the second-largest city west of Constantinople (Rome being the first.) The Roman legacy of Trier has been evident ever since: from the middle ages on, it contained the largest Roman edifices in all of Germany; they have been artifacts of daily life in the city from antiquity to the present. Yet in Trier's city museum, I found the above painting, which dates from 1559. In it, we see the buildings of medieval Trier being held aloft by a man wearing a turban. The painting's inscriptions explain: this man is, in fact, "Trebeta," the son of Ninus—legendary king of Assyria and husband of Semiramus. The painting goes on to claim that it was in fact this man, Trebeta, who, fleeing from Semiramus' sexual advances, wandered Europe until, finding a suitable landscape, founded the city of Trier with his own name. The painting is quite explicit about the significance of this event: the top-left plaque reads,

Two thousand and ninety-eight years before the birth of Christ, three thousand one hundred and seventy-seven years after the beginning of the world, and one thousand three hundred years before Rome, the old city of Trier was founded with the noble crown.

The last sentiment is even plastered across the central town square: this building reads, "Before Rome, Trier stood for one thousand three hundred years; it persists, and may it enjoy eternal peace, amen."

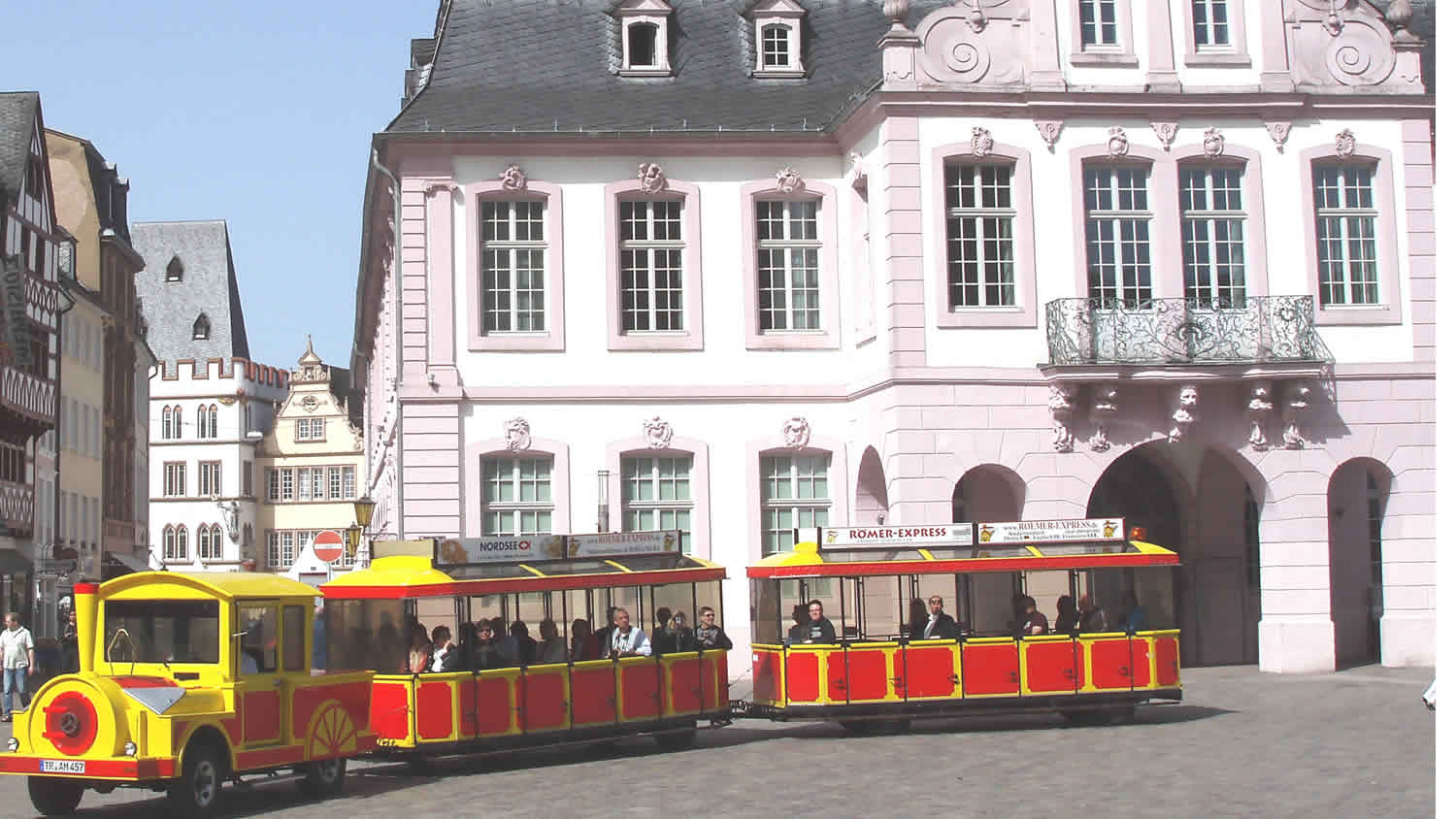

The need to be both Roman and not Roman—in other words, to invent a bizarre Middle Eastern foundation-myth (though in fact this was not an uncommon move in Eastern Europe)—is powerfully felt in Trier; it is the anxiety of knowing your heritage, but wishing to disavow it. This is the particular anxiety faced by those cities in Germany that owe their existence and powerful positions in the world to the legacy of the Roman imperial structure (i.e. most of Germany's major cities). And of course, the tables have now turned: for Rome is, in many ways, no longer the nemesis of Germany; rather, it is an incredibly popular tourist destination. Anything that links your city with the Roman Empire is now good for business. Thus, Trier, more than any city I have yet been to (including Rome), now bills itself as a Roman paradise—complete with men dressed as gladiators, restaurants serving "ancient Roman food," and the Römer-express, a thoroughly depressing street-train which is actually a disguised Jeep and which somehow passes itself as an authentically Roman way to experience Trier's "thrilling heritage." And lo, to cap it all, Trier has come up with a nickname for itself: Roma Secunda. Wenceslaus, it seems, was on to something.

|

| The Römer-Express in a flattering light. |

Comments

Post a Comment